This piece was written for my Visual Communications class taken in Third Year.

Masks Protecting Identities, but Hindering Resistance

Victoria Chiasson

20 November, 2013

People are driven to anonymity because they are scared of their government’s power over their futures. As a result, these protestors use masks to conceal their identities, in hopes to change the system without revealing who they are. Two noteworthy examples in today’s society are the Guy Fawkes mask associated with Anonymous, and the balaclava that is worn by Pussy Riot in Russia. Nevertheless, this paper proposes that these masks actually hinder the resistance movement both groups hope to achieve. In order to illustrate this thought, the masks will be discussed in two perspectives. First, this paper will use Karl Marx’s concept of the “Commodity Fetish” and how these masks – because of popularity – have become a trend within society. Next, the masks will be examined through Slavoj Žižek’s notion of how disguises are dangerous because they are embedded with an idea. However, since both groups have a variety of ideas, it is difficult to distinguish what central cause they are fighting for. Therefore, the de-individualization that stems from the use of masks is actually ineffective for protestors, because their activism is lost through the emergence of fads, overwhelming scope of ideas, and lack of humanization.

The Guy Fawkes mask and the balaclava were never initially created to become masks for protestors. They were appropriated by select individuals, and through their success in culture industries, have become a symbol of opposition and resistance. The origins of the Guy Fawkes mask derive from Alan Moore and David Lloyd in their graphic novel “V for Vendetta.” After the blockbuster movie in 2006, the mask was adopted by the hacktivist group Anonymous who established the mask as an icon of resistance. The balaclava can be traced back to the Crimean War, where they were used by British troops to defend themselves against the cold weather (Guy 2012). Pussy Riot now uses brightly coloured balaclavas to conceal their identity, and supporters will also don one to show their alliance with the musical group (refer to Figure 1).

Nonetheless, both masks have become commodity fetishes within society, as they are commonly seen as fads. Since a commodity fetish “refers to the process by which mass-produced goods are emptied of the meaning of their production (the context in which they were produced and the labour created them) and [are] then filled with new meanings in ways that both mystify the product and turn it into a fetish object” (Sturken 280), it is clear that both the Guy Fawkes mask and balaclava have become this. First, the Guy Fawkes mask has been disposed of its history of the failed Gunpowder Plot, and instead has been transformed into an item of anarchy. The balaclava is now mainly regarded in association with Pussy Riot, and not as a clothing item.

In an interview with CNN, Pyotr Verzilov, a husband to one of the band members of Pussy Riot, commented that the balaclava “[is] like the Guy Fawkes mask. You had people in the UK saying the Guy Fawkes mask is last year’s fashion — now you have to wear the Pussy Riot mask” (Sutter 2012). There are two key words in this statement that demonstrate why these masks have become commodity fetishisms in society. First he says “fashion” and that “now” you have to where the balaclava. This signifies why the masks prohibit effective resistance, the masks have inadvertently become a style each year, and if you are not wearing the newest, you will be out of trend. In order for resistance to maintain influence over the public, it needs to be constant, and not a short-lived fashion.

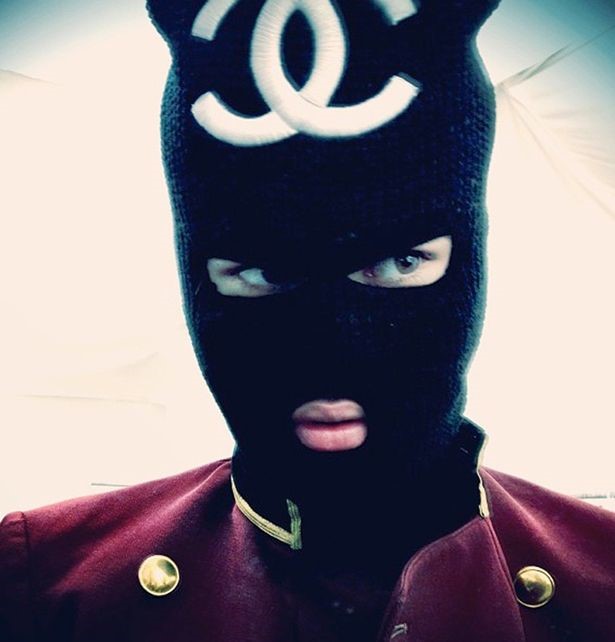

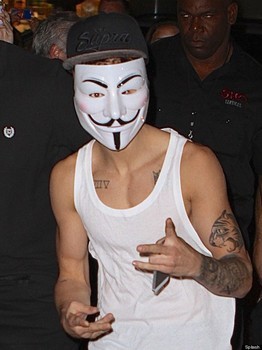

Additionally, messages are lost with the rise of popularity of these masks in society. This can be seen by celebrities appropriating the masks and transforming the message from political meanings to fashionable statements (Guy 2012). One notable example of this is Justin Bieber who has worn both the balaclava and Guy Fawkes mask (refer to Figure 2). It is fair to say that Bieber is not wearing these masks out of political alliance, since there is no record of him sharing his support for either cause. Besides, as a celebrity with major influence over society, they will usually acknowledge their support for such political movements.

The second perception this paper will analyze these particular masks is through Slavoj Žižek theory that the mask represents an idea. In commenting on Pussy Riot, he states that the band is dangerous because the balaclavas are “masks of de-individualization, of liberating anonymity. The message of their balaclavas is that it doesn’t matter which of them got arrested — they’re not individuals, they’re an Idea. And this is why they are such a threat: it is easy to imprison individuals, but try to imprison an Idea!” (Žižek 2012). True what Žižek states; however it is unclear exactly what ideas society should associate with these particular groups.

Specifically with the Guy Fawkes mask they are linked with: anti-corporate, anti-capitalism, cynicism towards government, anti-scientology, and the mask can be seen at any protest (Waites 2011). Alternatively, Pussy Riot is a feminist band who is Anti-Putin, and anti-corruption in Russia, as well as has recently added fighting for prisoners’ rights to their repertoire (Reevell 2013). Seeing as there are many ideas linked to these masks, it is hard to determine what protestors should fight for. Yes Žižek is right for stating that ideas cannot be imprisoned, but society will suffer if they conform to one identity. Governments should see the diversity of its citizens during times of resistance to see who they are affecting; to conceal one’s identity reminds the government of its power.

Instead, there should be a withdrawal on the importance of the mask as an idea, and rather an emphasis on the person that is behind them. Maria Chehonadskih provides an insight into why the mask, even though it may represent an idea, hinders the protest. The mask does not allow the audience to gain a sense of reasoning as to why the protestors have chosen to resist. In discussing Pussy Riot, she comments the influx of sympathy for the band after the de-masking of three band members. Chehonadskih explains that “this humanization strengthens the feeling of being protected, allows identification with the victim, distinguishes her or his story, and gets in touch emotionally. The mask, on the other hand, the absence of the victim’s face, conveys the impossibility of saying ‘I’” (Chehonadskih 7). The story of their resistance became international after the girls were unmasked and arrested. The world came to know Maria Alekhina, age 24, and Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, age 23, both mothers to five year olds. Due to this level of personal information, the public gathered in greater numbers to bring justice to the wrongful arrest of both women.

Applying this concept to the Guy Fawkes mask, the media represents the mask as a nuisance and as cowardly. The public cannot identify to the cause on a personal level because they do not have someone’s story to associate with. Perhaps this is why many protestors will go back to V’s story from the graphic novel, as this provides them with the satisfaction of knowing who they are fighting for, even if he happens to be fictional. The personification of V has also been attributed with Julian Assange (refer to Figure 3) after his notorious website WikiLeaks (Johnston, 2010). This explains why the group needs to demask when addressing governments and corporations, because they too can become figures of rebellion like Julian Assange, instead of having someone else take the role.

Furthermore, because of the wide success following the V for Vendetta film, the masks have become in wide demand. Understanding that Anonymous promotes anti-corporation, and anti-capitalism, it is hypocritical for the group to buy these masks. Every time a mask is purchased, Warner Brothers profits from royalties since they own the copyright. Additionally, masks are said to be manufactured in sweatshops (refer to Figure 4), which contradict what the group is fighting for: human rights.

This paper suggests that rather than using disguises, protest groups should move towards a unifying symbol that carries their message for the world to see. A successful symbol in the last decade has been the red felt square worn by student protestors in Quebec. Olivia Messer describes the red felt square as “a symbol of the student movement and the fight against poverty in Quebec. As many explain it now, the safety-pin clad symbol is inspired by the French phrase ‘carrément dans le rouge’ (meaning ‘squarely in the red’)…a wordplay on students trapped in debt caused by tuition hikes and cuts in bursaries” (Messer 2012). From this statement, it is clear that there was thought put into the making of this symbol, and has definitive meaning.

A small, distinct symbol provides more significance in today’s society opposed to masks, because it sparks persons to look up what these symbols mean if they have not come across them before. One of these instances, continuing with the red square example, was on Saturday Night Live back in May 2012. Band members from Arcade Fire wore the red felt square on their clothing during a performance with Mick Jagger (refer to Figure 4). The Huffington Post summed up the symbolic act by stating: “Those red patches the band were wearing weren’t fashion statements, but very pointed acts of protest in support of Quebec students…” (Huffington 2012). Unlike masks worn by celebrities for fashion statements, these symbols have both drawn the attention of viewers watching SNL to make note of the image, and also look up what it was for. In turn, discussion was ignited for their act, and attracted more awareness to the political movement. With more awareness to such causes, governments are forced to respond.

There is also the benefit of being able to incorporate the symbol into everyday wear, bringing the message into any institution in an acceptable manner. This is where Anonymous’ Guy Fawkes mask and Pussy Riot’s balaclava are lacking, because it is unconventional to wear masks in places of work, school, or inside any building. Therefore, their political movements are prohibited from impacting society, as society can only witness the political movements outside. With the use of a small symbol, “there’s sophistication to the strong but silent symbolism and the fact that an individual can so easily incorporate their particular political view into their day-to-day dress. The red badge affirms the wearers unity while allowing them to express their individuality” (Jackson 2012). If one were to attempt to show their political alliance to Anonymous or Pussy Riot during their everyday schedule, they would be asked to take off their masks and to continue on with their day. This would stop the political action, because they would be unable to express themselves.

Consequently, it is clear that fads, breadth of ideas and de-humanization cause protests to lose their meanings, as the mask prohibits ideas from fixing in society. As Karl Marx’s theory of commodity fetishism shows, these masks become fashion statements instead of political icons through the rise of popularity. Justin Bieber exemplifies this by appropriating both of the groups’ masks and using it for his own self-loving motivation (which has since upset Anonymous because of the association of Guy Fawkes with Bieber). The notion that ideas are embedded in masks from Slavoj Žižek is true, but with both groups there is a plethora of ideas that protestors become lost in exactly what they are fighting for. Moreover, because of the scope of causes, there becomes more room for the groups to be hypocritical. Finally, the mask makes society into a collective, which draws away from the individualization that is important to remember. Pussy Riot’s international success was only possible after society learned who they were. Symbols are needed for groups to create awareness about their political concerns to humanity, but rather than disguises, there needs to be a small icon that can penetrate institutions. The red felt square is a prime example of this, as seen through Arcade’s Fire support on Saturday Night Live. As V told Evey, “people shouldn’t be afraid of their government. Governments should be afraid of their people” (Moore 1989). But with the increasing prevalence of anonymity, masks only re-establish that individuals are fearful when standing up for political and social reasons.

Appendix

Figure 1: Pussy Riot Supporters

Figure 2: Justin Bieber wearing Chanel Balaclava (top) and Guy Fawkes Mask (bottom)

Figure 3: Julian Assange mixed with V, from Cart1 at

http://www.bloodyloud.com/street-portraits-cart1/

Figure 4: Guy Fawkes masks being manufactured in a sweatshop

http://blogs.telegraph.co.uk/news/marthagill/100244704/anonymous-have-been-exposed-as-hypocrites-who-use-sweatshops-watch-them-try-to-wriggle-out-of-it/

Figure 5: Arcade Fire (wearing the red-felt square) with Mick Jagger on SNL May 19 2012

Works Cited

Chehonadskih, Maria. “What is Pussy Riot’s ‘Idea’?” Radical Philosophy November/December (2012): 2-7. Print.

Guy. “The Dangers of the Fashionable Balaclava.” Weblog posting. Way We Wore. 12 June 2012. Web. 12 Nov. 2013.

Huffington Post. “Arcade Fire Support Quebec Student Protests on Saturday Night Live, Join Likes of Michael Moore, Anonymous.” The Huffington Post Canada. TheHuffingtonPost.com, Inc. 20 May 2012. Web. 11 Nov. 2013.

Jackson, Sacha. “Seeing Red.” Weblog posting. Worn Blog. 2012. Web. 12 Nov. 2013.

Johnston, Rich. “Julian Assange, Wikileaks and V For Vendetta.” Weblog posting. Bleeding Cool. 16 Dec. 2010. Web. 11 Nov. 2013.

Messer, Olivia. “Squarely in the Red.” The McGill Daily Culture. The McGill Daily, 31 March 2013. Web. 11 Nov. 2013.

Moore, Alan, writer. V for Vendetta. Illustrated by David Lloyd. Colored by Steve Whitaker, Siobhan Dodds, & David Lloyd. Lettered by Steve Craddock. London: Quality Comics, 1989. Print.

Sturken, Marita and Lisa Cartwright. Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. Print.

Sutter, John D. “Jailed Punk Band Pussy Riot Pushes Free Speech Limits in Russia.” CNN (2012). Web. 09 Oct. 2013.

Reevell, Patrick. “Jailed Pussy Riot Member Launches Fight for Prisoners’ Rights.” Rolling Stone. Jann S. Wenner, 17 Oct. 2013. Web. 11 Nov.2013.

Waites, Rosie. “V for Vendetta Masks: Who’s Behind Them?” BBC News Magazine. British Broadcasting Corporation, Oct. 2011. Web. 12 Oct. 2013

Žižek, Slavoj. “The True Blasphemy.” http://chtodelat.wordpress.com/2012/08/07/the-true-blasphemyslavoj-zizek-on-pussy-riot/. 12 Oct. 2013.